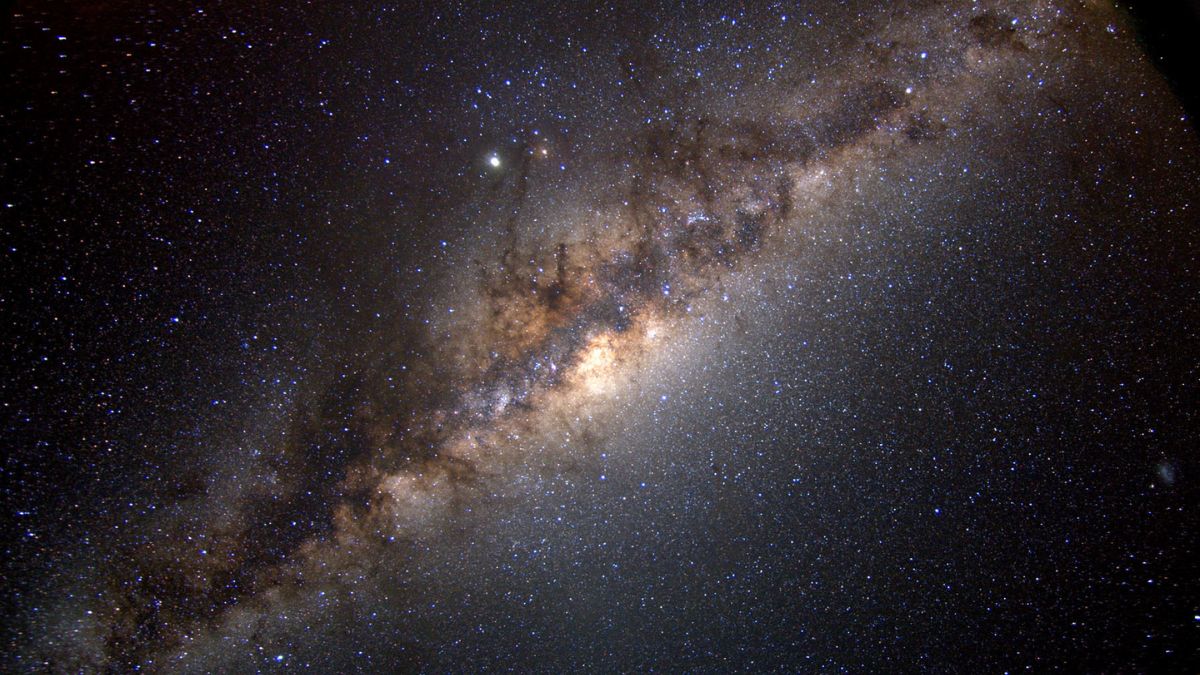

For over a century, we believed we were on a cosmic collision course. The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies—two spiral giants hurtling toward each other at about 100 kilometers per second—were expected to meet in a dramatic merger roughly 4.5 billion years from now. This “inevitable” encounter has inspired everything from academic research to sci-fi epics. But now? That story’s shifting. Thanks to new astronomical models, the future looks a lot more uncertain.

Milkomeda

The classic prediction went like this: our galaxy and Andromeda would smash together, destroying their graceful spiral arms and forming a single, massive elliptical galaxy. Scientists even gave it a name—Milkomeda.

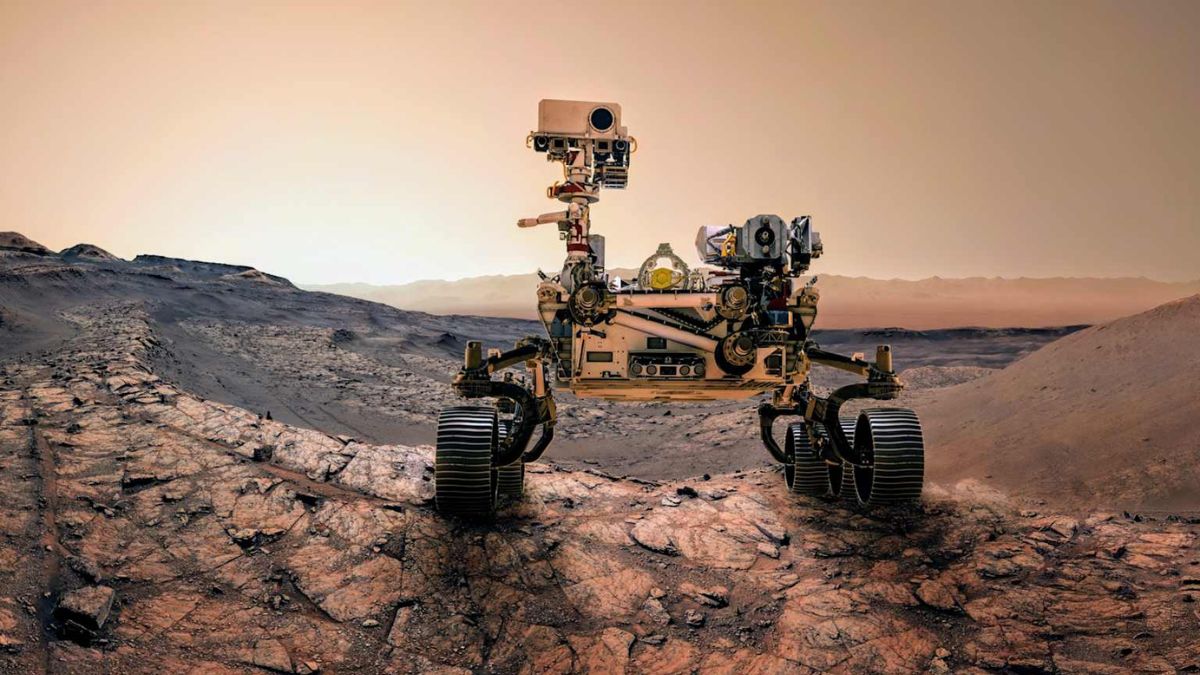

That merger wouldn’t mean the end of our planet (at least, not directly). Despite the sheer scale of the event, the chances of actual stars colliding are slim. Instead, Earth’s future hinges more on the Sun’s own timeline. In about 5 billion years, it will balloon into a red giant, possibly swallowing Mercury, Venus, and even Earth in the process.

Astronomer Carlos Frenk once compared galactic mergers to “cosmic fireworks,” where central black holes get supercharged, spitting out radiation before swallowing everything near them. Milkomeda, if it ever forms, could be one dazzling show.

Satellites

So, what’s changed? A recent study published in Nature Astronomy has thrown a wrench into the Milkomeda narrative. For the first time, researchers factored in other major players in our cosmic neighborhood—the Local Group. We’re talking about the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) and the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), two massive satellite galaxies.

Till Sawala, an astrophysicist from the University of Helsinki, explains that these bodies exert subtle but critical gravitational pulls. M33 nudges Andromeda closer to us, but the LMC does something more dramatic—it tugs the Milky Way away from Andromeda’s path.

That means our galaxy’s route through the universe isn’t as straightforward as we once thought. The gravitational dance now looks more like a messy tango than a head-on collision.

Odds

So what’s the likelihood of this once-“inevitable” crash happening? After running 100,000 simulations with 22 different variables (masses, velocities, and positions), scientists found that the odds of a Milky Way-Andromeda collision within the next 10 billion years are around 50%. Even more surprising? The previous prediction—that they’d collide in 4 to 5 billion years—now carries only a 2% chance.

Let’s break it down:

| Scenario | Probability | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Early Collision | 2% | 4–5 billion years |

| Delayed Collision | ~48% | 7.6–8 billion yrs |

| No Collision (Close Flyby) | ~50% | N/A |

Possibles

This leads us to two likely outcomes. In the first, the Milky Way and Andromeda gradually lose energy as they spiral around each other, eventually colliding after about 8 billion years. In the second, they come close—close enough to feel each other’s gravitational pull—but not enough to merge.

Instead of fireworks, we might just get a cosmic “high five.”

Interestingly, a merger is expected—just not with Andromeda. The Milky Way is on a nearly certain collision course with the LMC, estimated to occur in about 2 billion years. According to Frenk, that could significantly change the shape and structure of our galaxy.

So, while the Milky Way’s ultimate fate is still up in the air, one thing’s clear: our galaxy is heading into uncharted territory. And the universe, as always, has its own plans.

FAQs

Will the Milky Way collide with Andromeda?

New data shows only a 50% chance over 10 billion years.

When is the earliest possible collision?

Only a 2% chance of it happening in 4–5 billion years.

What is Milkomeda?

It’s the name for the potential Milky Way-Andromeda merger.

Will stars crash during the merger?

Very unlikely, due to the vast space between stars.

Is the Milky Way merging with another galaxy first?

Yes, it’s expected to merge with the LMC in 2 billion years.