What if I told you one single image managed to contain nearly a million galaxies? That’s not just a jaw-dropping photo—it’s a cosmic record-breaker. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), in partnership with the legendary Hubble, has captured a sweeping, high-resolution snapshot of the night sky that’s nothing short of intergalactic art.

But beyond the beauty, it’s a scientific goldmine that’s already challenging what we thought we knew about the early universe.

Snapshot

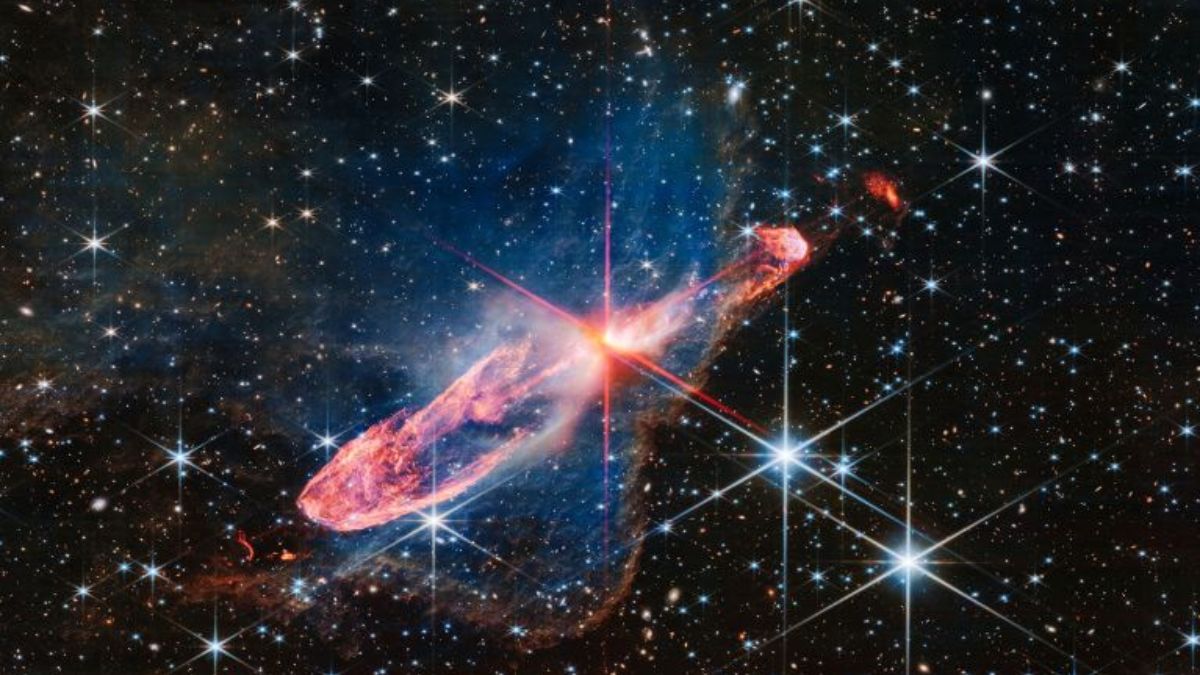

Say hello to the COSMOS-Web field, the largest image ever taken by JWST. This isn’t just a wide-angle view of space—it’s a masterpiece stitched from over 10,000 exposures. Covering 0.54 square degrees (think two and a half full Moons), this cosmic mosaic holds a jaw-dropping 800,000 galaxies, not to mention 1,678 galaxy groups. That’s more than any previous survey has managed to detect in one go.

Each pixel in this image represents not just stars, but galaxies—some of them from a time when the universe was less than a billion years old.

Technique

Capturing such a massive image was no small feat. JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) scanned the sky in a 12×9 tile formation, carefully overlapping each shot to cover detector gaps—kind of like playing cosmic Tetris.

Back on Earth, scientists turned 40 terabytes of raw data into this colorful mega-mosaic. They filtered out cosmic rays, aligned star fields down to milliarcsecond precision, and corrected color tones so cooler stars appear ruby-red and hotter stars lean teal-blue.

But Webb doesn’t see everything. That’s where Hubble came in, adding optical data that Webb’s infrared vision misses. When layered together, the result is a time-traveling image where ancient galaxies 500 million years after the Big Bang appear next to nearby spirals just 50 million light-years away.

Cluster

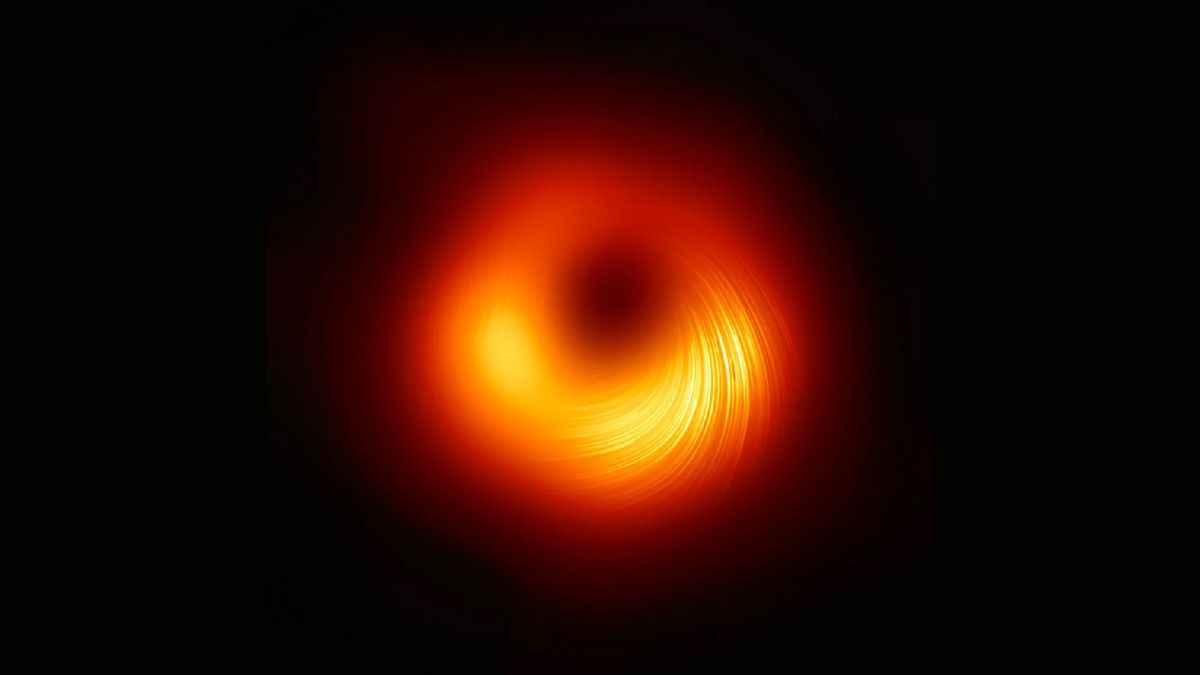

What really catches the eye in the image is a glowing gold-tinted knot near the center. That’s a galaxy cluster so massive it weighs as much as several hundred trillion Suns.

X-ray maps from ESA’s XMM-Newton show it contains hot gas trapped by gravity, while Webb reveals individual galaxies orbiting the core, like bees around a hive. This isn’t just eye-candy—it’s a real-time look at a cosmic city in the making.

Galaxy clusters like this are important because more than half of today’s galaxies live in similar environments. Studying how this cluster formed tells us how dark matter—and even the structure of the universe—came to be.

Surprise

Here’s the kicker: JWST’s image shows way more low-mass galaxies in the early universe than standard cosmological models (like ΛCDM) predict. Like, ten times more.

That’s not a small error—it’s a cosmic curveball.

Some astronomers think these galaxies may appear brighter because they’re full of dusty star-forming regions. Others argue that it’s time to rethink our theories—maybe dark matter behaves differently than we thought, or maybe the rules for how stars form in early galaxies need an update.

Either way, it’s the kind of puzzle scientists live for.

Humans

Behind every pixel is a human story. Graduate student Anya Malik coded the image alignment tool, calling it “mosaic-tetris.” At 2:57 a.m., she got the Slack message: Tile 432 matched. RMS error: 0.004″. That’s basically pixel-perfect.

From Santiago, her teammate Luis Robles sent a GIF of fireworks. For eight weeks, they slogged through data, debugging one tile at a time. “When the final image loaded,” Malik recalls, “we zoomed in and got lost. Every click was a new galaxy.”

That’s the magic of this project—it’s a blend of cutting-edge tech and deep human curiosity.

Future

This image isn’t the end—it’s just the beginning. Webb’s spectrographs will now analyze the chemical fingerprints of the galaxies in the cluster, revealing when and how their stars formed.

In 2026, the Vera Rubin Observatory will start its decade-long survey of the southern sky, layering time-based data onto Webb’s image. This could catch cosmic events like supernovae or black hole flares happening in real time inside galaxies that Webb already photographed.

Looking further ahead, ESA’s Athena X-ray telescope will track how hot gas flows through the cluster, testing alternate theories of gravity and further probing the mysteries of dark matter.

Involve

Even more exciting? You don’t need a PhD to contribute. The COSMOS-Web image is open-access, and the viewer lets anyone zoom in, look, and tag strange features.

Students, teachers, amateur astronomers—even high schoolers—can help identify gravitational lenses or rare arc-shaped galaxies. If their finds are unique enough, they might even get co-author credit on scientific papers.

Because sometimes, all it takes to make a discovery is a curious eye and a good internet connection.

FAQs

How many galaxies in COSMOS-Web?

Roughly 800,000 galaxies were captured in the survey image.

What is COSMOS-Web’s image size?

It spans 0.54 square degrees—about 2.5 full Moons.

Why is JWST’s image important?

It reveals unexpected galaxy density and challenges old models.

Who worked on the image alignment?

Grad student Anya Malik led the alignment coding effort.

Can the public explore COSMOS-Web?

Yes, it’s open-access and citizen scientists can contribute.