Not everything in space follows the rulebook—and that’s what makes discoveries so exciting. In the depths of our galaxy (and even beyond it), scientists are now turning their attention to mysterious objects that aren’t quite stars and aren’t exactly planets. For decades, they were considered cosmic misfits. But thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), these so-called “failed stars” might actually be secret planet-makers.

Hybrid

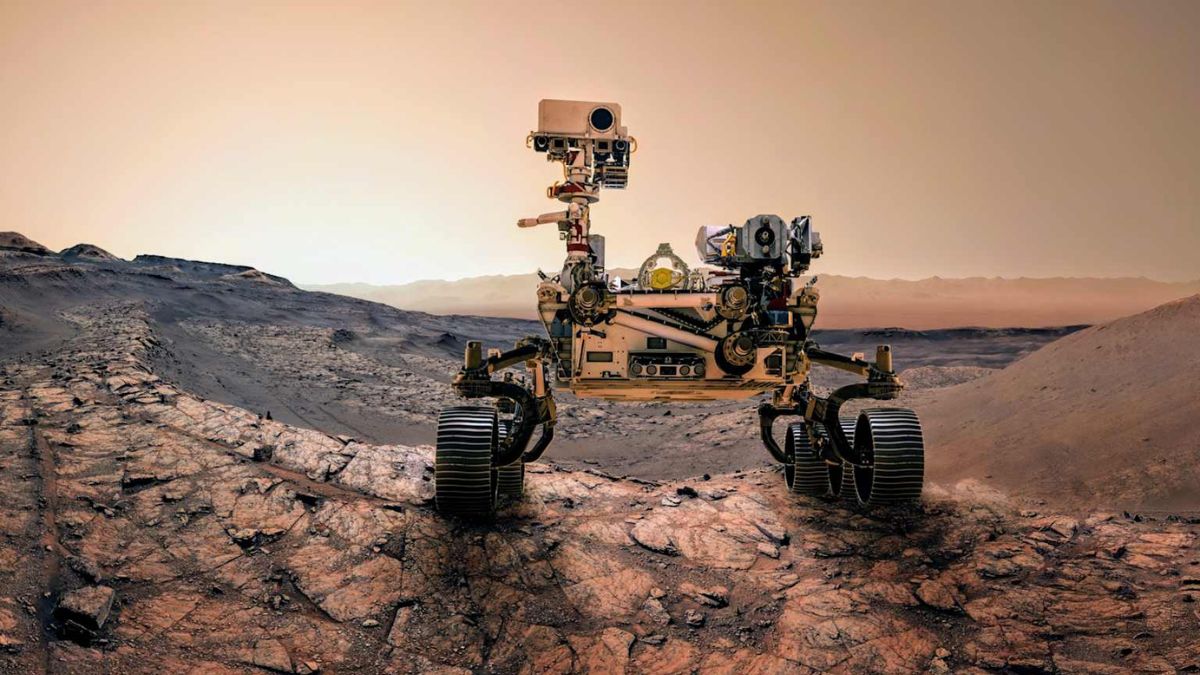

We’ve always believed that planet formation happens around stars. It makes sense, right? Young stars form from collapsing clouds of gas and dust, and as they spin, they create surrounding disks that birth planets. This has been the working theory since the days of the Hubble Telescope’s first images of the Orion Nebula.

But now, JWST is flipping that idea on its head. While scanning the Orion Nebula—a nearby stellar nursery—scientists noticed something unexpected. Some protoplanetary disks weren’t orbiting stars at all… but rather brown dwarfs.

Misfit

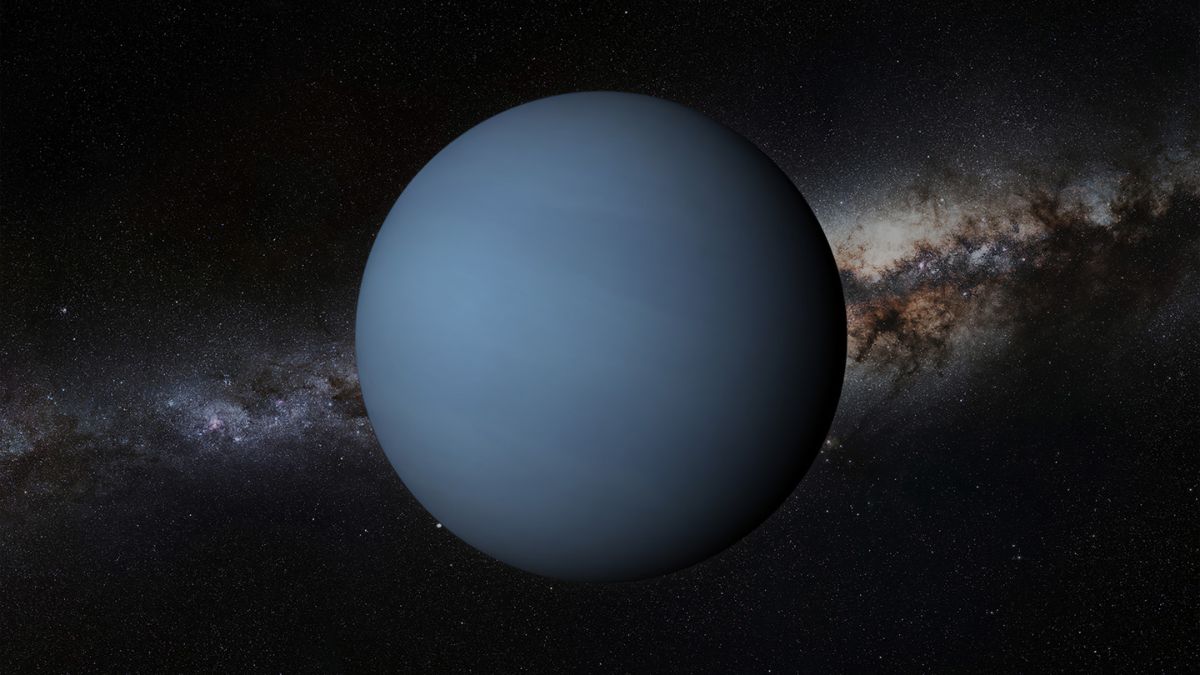

Brown dwarfs are strange. They form like stars, from collapsing clouds, but they don’t get big or hot enough to ignite hydrogen fusion—the process that powers true stars. So they end up in limbo. Too massive to be a planet, not massive enough to shine like a star.

That’s why they’ve earned the not-so-glamorous nickname “failed stars.” But the more we look at them, the more they look like something else entirely: hidden architects of planetary systems. And JWST is giving us the clearest view yet.

Findings

In the Orion Nebula alone, JWST has revealed at least 20 brown dwarfs with disks of gas and dust spinning around them—just like the early solar system had. Some of these dwarfs are incredibly small, with masses equivalent to only 5 times Jupiter.

A couple of them are even hovering right at the boundary between brown dwarfs and tiny stars, making their classification tricky. But the point is clear: brown dwarfs can have the raw material to form planets.

This isn’t just wild theory anymore—it’s being seen with our own eyes. Kevin Luhman, an astronomer, points out that this could help fill in huge gaps in our understanding of how these oddball objects form and how they relate to stars and planets.

Beyond

Even more exciting? JWST has found similar brown dwarf candidates far outside the Milky Way. It turned its gaze toward NGC 602, a young star cluster in the Small Magellanic Cloud—a nearby galaxy. What it saw was incredible: 64 brown dwarf candidates, with masses between 50 and 84 times that of Jupiter.

These are the first brown dwarf candidates ever seen beyond our galaxy. And because the Small Magellanic Cloud has a metal-poor environment—similar to the early universe—it gives us a peek at what the conditions were like billions of years ago when the first stars and planets were forming.

Potential

Elena Sabbi, an astrophysicist on the JWST team, says that studying these ancient, low-metal brown dwarfs could unlock major clues about the early universe. If they can form planets now, maybe they could back then too.

All this forces us to ask some pretty mind-bending questions: If brown dwarfs can make planets, are they still “failed stars”? Or are they something else entirely—a whole new category of cosmic creators?

And the story doesn’t stop there. With NASA continuing to uncover mysterious objects beyond the Milky Way, this could be just the start of a new chapter in how we know the birth of planets… and perhaps even life itself.

FAQs

What is a brown dwarf?

A brown dwarf is a failed star—too small to sustain fusion.

Can brown dwarfs form planets?

Yes, JWST found protoplanetary disks around them.

Where were brown dwarfs observed?

In Orion Nebula and the Small Magellanic Cloud.

How big are brown dwarfs?

Between 13 and 80 Jupiter masses, roughly.

Why are brown dwarfs important?

They help us understand planet formation in new ways.